Celeste is a difficult game.

And yet, despite its difficulty, at no point in my playthrough of the game have I ever felt stuck, or that any particular challenge is unfair.

Celeste is designed to tempt you into trying again, to make persistence the only logical option. But with difficulty being one of the most contentious design topics out there, how does the game manage to ride the line between challenge and frustration?

Let’s find out!

Player-Led Difficulty

Everyone already knows Celeste is difficult. I was late to play this now-classic indie platformer so I’ve only just gotten a handle on how difficult the game really is. Surprisingly, this challenge is mostly self-inflicted.

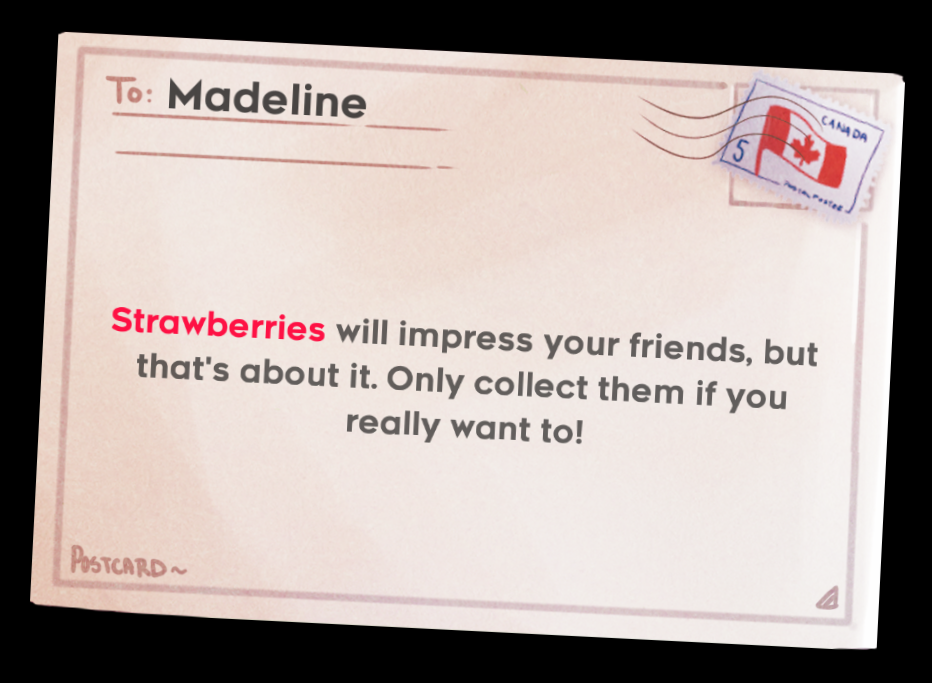

Upon completing the first chapter, the player is told that there are strawberries to collect throughout each level. However, unlike many games, Celeste makes a point to state how these strawberries are entirely optional.

You can complete the game without collecting a single one.

Damn, now I want to collect all of them!

This immediately does two things:

- It lets the player know that if they come across any challenge for a strawberry that is too difficult for them, they can leave it knowing that it will not affect their progression.

- It makes the strawberries instantly 10x more appealing, as these aren’t just collectables, these are VANITY collectables. If you manage to collect a strawberry, it’s because you wanted to, not because the game required it.

Whilst there are a few other types of collectable within the game that do lead to extra content, it’s the strawberries that the player will repeatedly find during their climb. Some of the sequences to reach these strawberries are tough.

Also, the path through each level is not always linear.

Many levels include multiple paths that cross and loop around each other, and since it’s not always clear which is the ¨correct¨ path, you are certain to encounter these strawberries along the way.

This non-linear level design creates a sense of exploration, with the player calling the shots. If you’re the detail-oriented type you can choose to peak into every corner, testing each wall for a hidden entrance. Or for a speedy playthrough you can stick to the main path, attempting to collect strawberries as you find them but not stressing if you can’t after a couple of tries.

By setting your own level of challenge, the player is actively engaging with the overarching theme of the game about overcoming internal barriers and “Climbing your own mountain”.

Just as the Celeste mountain adapts to put pressure on each character’s personal difficulties, the game itself adapts to each player’s skill level by keeping the hardest challenges enticing, but optional, and never artificially preventing the player from advancing.

Forget ludo-narrative dissonance, this is LUDO-NARRATIVE ALIGNMENT!

Making Failure Easy

When the player dies by falling off the bottom of the screen, being crushed by a moving block, or touching one of those cute little red guys from the hotel level, Celeste uses a few techniques to make this process impactful, but not too painful; achieving the perfect balance for learning from your mistakes.

I still don’t know what these guys are, but aren’t they cute?

As you play Celeste, you will die. Many times! Because of this, you will spend a substantial amount of time thinking about why you died and how to improve your next attempt. This is perhaps the most important moment in a difficult game like this.

Getting this moment right is key to keeping players engaged with the game despite the repeated attempts needed to beat a level.

If the player is given too much time to wait until they can play again, they will get bored. Do this many times, and they will begin to resent both dying and you, the developer. They will be hesitant to try new strategies, optional paths, or anything they deem as difficult.

On the flip side, if the game restarts too quickly, there is no time for the player to understand why they died and to think about their next approach. This encourages a reckless “Brute Force” play-style that takes away from the player’s feeling of agency, shifting it towards a sense of luck.

Neither of these outcomes are ideal for a game about overcoming personal challenges, so how does Celeste handle this?

The first thing you see when you die as the player is a rotating ring of orbs around the position where they died. Apart from being aesthetically pleasing, it serves multiple purposes.

- The rotating, pulsing orbs attract the attention of the player, so they don’t miss the information if they are looking elsewhere.

- The orbs form a ring, so rather than obstructing the death zone, they highlight the exact point where the player died. The message is clear: “Next time, AVOID THIS THING!”

- The colour of the orbs indicates how many dashes the player has left. This simple design choice is often the secret to figuring out a level’s sequence. If you die at a spot where you needed to dash, but you didn’t have one ready, perhaps there’s a way to get to that same spot without using your dash early? If you died but still had a dash left? Use it next time!

The visuals are nice, but man, the sound effects are incredible too!

All of this information gives the player a crystal clear “What, Where, Why” as to how they died, all within about half a second. That’s a decent amount of info, but what do we do with it all?

The game then fades to black with a simple slide transition. At this point, it’s reloading the room, but it also gives the player a moment to internalize what they saw just a moment ago. This is enough time for the player to take a breath, and for the brain to figure out “Maybe I should try it again this other way?”

This all comes together to create a death sequence where; instead of being bored or overstimulated, the player is refreshed and keen to try again with a new strategy, or they can try the same way again, but with renewed focus.

Be Proud of Trying

One might ask the question “Why are we trying to make difficulty accessible at all?”.

The answer is a rather subjective one – everyone may have their own answer – but for many players, myself included, one of the biggest draws to a challenge is simply the experience of going from “I can do this…” to “I did it!”.

There is value in testing your limits, choosing to take on a challenge, and persevering through difficult moments. This is the spirit of Celeste and it is present throughout the entire narrative.

Maddie, the game’s protagonist, battles through multiple manifestations of her internal struggles to climb the mountain, for no reason other than to reach the top.

“I need to do this.” she says.

The desire to improve and conquer our insecurities is an incredibly motivating force, and it allows us to grow and change as people.

Me realising I will need to play for another 10 hours to reach 100%

Perhaps one of the simplest but most effective ways Celeste embodies this idea is in its home page. The game lists your deaths right next to your accomplishments. The number of times you died is just as important as how many strawberries you collected.

Died 165 times, kept climbing anyway ; )

It’s not difficult to extend this metaphor to real life.

In our lowest moments, insecurities can keep us from acting, we beat ourselves up for our mistakes, we carry too much emotional weight from “not being good enough” and hold ourselves back in fear of falling.

Celeste shows us another way.

Be proud of your mistakes, because they mark every time you try.

<3