Humans love stories. We are the storytelling ape after all. Our ability to consume and adapt to complex information gives us both our survival advantage, one of our most unique experiences as a species. Stories have been delivered for millennia through oral storytelling, theatre and writing, and now in the modern day we also have access to film, and more recently, videogames. How have these newer mediums affected the way we tell stories?

Games offer a unique style of storytelling, as the player of the game always has some level of agency, and it is through how they use that agency that the story is told. But without direct control over what the player sees or does, how do you ensure the player has the experience you are looking to provide, without just turning your game into a movie or book?

The secret lies in how you use game mechanics to enhance the narrative, playing to the strengths of the medium. We can still use classic tools such as metaphor, symbolism and story structure, but we can also add player choices (and their consequences) and gameplay features to guide the player through an experience you’ve designed.

So where does the game mechanic end, and narrative or even metanarrative begin? How do we use game mechanics to tell a story that resonates with the player?

It depends on what kind of story you’re trying to tell, and how you’d like to tell it. You can tell a story explicitly, either by dialogue, text narration, or other direct method, or you can tell a story implicitly through gameplay mechanics, player choices, and metaphor. Neither method is better than the other, its about how you use them.

The best games use a combination of both. I believe Subnautica is a fantastic example of this, as it uses dialogue and text logs to give you specific game context, but the larger narrative is guided by the players mechanical progression and their urge to explore deeper. (You can check out my blog on the topic here: https://jackbriggs.dev/subnautica-guiding-natural-exploration/)

The FromSoftware Souls series is a masterclass in gradual, mysterious worldbuilding, using exploration and item collection an essential part of the core narrative. Then there is also the metanarrative relating the player’s drive to keep trying and never give up, to the unstoppable force of change in the world that will end the Age of Fire (Or allow it to continue for another generation).

God of War & Ragnarök (The new ones) make conversation between characters whilst walking through beautiful scenery a core “mechanic” of the game, which is heavily juxtaposed against how violent the fighting is. That contrast is how the game is paced mechanically, but it also represents the conflict of Kratos’ later life, wanting peace, but needing to fight.

“Lamb’s Cress… I’m the ******* God of War!”

Chants of Sennar shows the value of translation and breaking down language barriers, as you take part in doing exactly that. I’ll be talking more on that game in another post to come!

There are a few other games I’d like to try that I’ve heard combine narrative and gameplay mechanics excellently.

- Journey for it’s implicit storytelling and silent narrative.

- Disco Elysium for game mechanics that impact the story, and great writing.

- Slay the Princess, for its unreliable narrative and interesting premise.

Emotional Impact

So why would you choose to put the extra effort in to tell a story through game mechanics rather than just audio or text? Primarily it comes down to emotional investment. Games have a unique opportunity of allowing the player to both experience and impact the story they are being told. They have agency. If you can show the player a reason to care, and then show them they have the power to actually change the outcome, that is often much more engaging than just being “told” a story.

Here’s a good example of a game moment that could have been a cutscene, but by adding a simple game mechanic the moment became much more impactful: Dead Space 2’s eye needle scene.

No one needs to see that scene again, so instead here’s Momo, our cat. 🙂

It’s a horror game, they want the player to be spooked. They could have just shown the main character getting eye surgery, and told the player “this is a risky procedure”, which would have made the player say “Oh no, I hope this goes well”.

What they did instead, was put the controls of the needle into the hands of someone who is most likely NOT a surgeon (very scary), and made it work narratively by giving Isaac (and therefore the player) control of the machine to do his own surgery. Even though the end result is the same in terms of story (Isaac get a needle in his eye) It’s a much more impactful moment because the player was both involved AND responsible for the outcome.

Gameplay Progress & Narrative Progress

We’re not just limited to singular moments in bring narrative and gameplay together. The Dead Space example is somewhat “gimmick-y”, as it is a one and done scene that is very impactful, but doesn’t necessarily intertwine with the rest of the game’s mechanics.

When designing mechanics that drive a narrative and span a large portion of the game, the “Mechanics as Metaphor” idea can be more helpful. Game mechanics can represent a core aspect or idea within your game’s story, and act as a catalyst for the player to engage with that theme.

Sometimes this can be very direct, like point-based social relationship systems, (+5 relationship points with this character because you spoke with them, yay!), or they can be more subtle, (To use a previous example: The undying nature of the Chosen Undead of Dark Souls represents both a personal emotional journey of perseverance for the player, but also the inevitability of the end of the Age of Fire)

To understand what game mechanics you can implement to tell a story, it may help to first understand the structure of the story you are trying to tell.

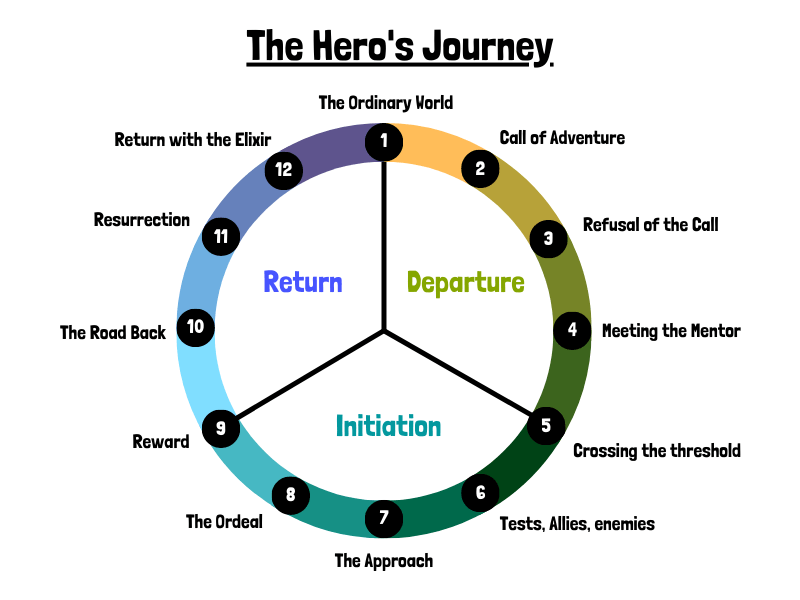

Most stories follow a similar structure, such as the Hero’s Journey or the Three-Act structure. (Or something like a Greek tragedy but you see less of those these days as they end sadly and there isn’t as much of a modern appetite for that in commercial products). Knowing your story’s structure, you can use game mechanics to make each part more impactful.

Here’s the general structure of “The Hero’s Journey”:

source: imagineforest

Act 1: Departure

- The Ordinary World

- The Call of Adventure

- Refusal of the Call

- Meeting the Mentor

Act 2: Initiation

- Crossing the First Threshold

- Tests, Allies, and Enemies

- Approach to the Inmost Cave

- The Ordeal

- Reward (Seizing the Sword)

Act 3: Return

- The Road Back

- Resurrection

- Return with the Elixir

You can take both the overall themes of your story and use mechanics to represent those (If the story is about someone finding their inner strength, make the player feel stronger as they progress through the game, more powers, easier time with old enemy types etc) AND you can take specific segments of the story structure and build mechanics around those too. As an example, let’s take the steps 4 & 5: “Meeting the Mentor” and “Crossing the First Threshold”.

One common way to give the Hero a motivation to actually go on his adventure, is to have him be very attached to his Mentor, and then have the Mentor die at the hands of the main villain or problem. You could just show all this in a cutscene, but wouldn’t it be more emotionally impactful for the player if they spent a good amount of time playing the game alongside the Mentor? You spend a good 2 hours of gameplay receiving tutorials from and working alongside the Mentor, make them super likeable and wholesome, and then kill them off. How awful! Now both the Hero the player have an emotional motivation to go on the journey.

You can do this sort of thing with any of the points in the story. Ask yourself: “What emotion do I want the player to feel here, and how are the game mechanics helping me do this?”

Note: It might also help to read into Ludo-Narrative Dissonance, to avoid some of the major pitfalls where game mechanics and story don’t match. One of my favourite examples is the “Batman doesn’t kill”, rule, and then the player can just throw a person off a building. Uncharted is another good one, Nathan Drake is just a chill dude adventurer, a normal guy, and also slaughters hundreds of hired militia men with zero repercussions.

Thanks Mr Drake!

Hooks and Avoiding Cliché

When introducing game mechanics that reinforce the narrative of a game, its fairly easy to fall into the same solutions that others have done before. To avoid feeling derivative, it’s important to understand the “Hook” of your game. What is it that you are doing that others are not? It could be an interesting mechanic, a unique story setting, a cool visual style, or anything that makes your game not like the others.

Something being done before doesn’t mean its inherently bad, the fact that we have genres comes from there being certain styles and similarities between media.

Take JRPGs for instance, they are all practically some form of “Hero goes on adventure, meets friends, solves problems, then defeats God with the power of friendship”. But each one has something unique that makes it worth playing:

- Xenoblade Chronicles has a unique combat system.

- Final Fantasy was super early to the market, and has some great world building.

- Dragon’s Quest has incredibly strong visual theming, and memorable monsters (It was also there first).

- Chrono Trigger has time travel and multiple endings.

- Earthbound has children as the protagonists, and dream-like, reality-bending worlds.

- Persona has you shoot yourself in the head to summon your powers. (And is also a great combo of relationship building & dungeon exploring mechanics).

The JRPG genre itself is based on “The Hero’s Journey” story arc. It’s not cliché, so much as it is a consistent way of telling a story for a rewarding payoff.

In summary:

- Use story structure for familiarity and to give you a starting place to design your mechanics.

- Add a unique “hook” to get people interested in your game.

- Highlight one-off moments with novel mechanics to make them more impactful.

- If stuck, ask yourself: “What emotion do I want the player to feel here, and how are the game mechanics helping me do this?”

Extra Resources:

Extra Credits is a great channel for more info on this topic: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4QwcI4iQt2Y They have a bunch talking about it

Game Makers Tool Kit also has a great one on narrative through Level Design specifically: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RwlnCn2EB9o

Leave a Reply